Bribery and corruption in context

As the UK Bribery Act 2010, the world’s strongest piece of anti-corruption legislation reaches its tenth year, we look back on how the Bribery Act came to be.

Corruption you can see

The case of John Poulson provides an example of how small-scale bribery can, if unchecked, build up into a multi-million pound industry. Over 30 years Poulson, though not a qualified architect, and starting with just a £50 loan, built up the largest architectural practice in Europe through the corrupt purchase of local government contracts in northern England, and of contracts for the re-development of major railway termini through bribery of a British Rail employee, Graham Tunbridge. The bribes involved were not always large. When Tunbridge became Estates and Rating Surveyor for BR Southern Region, he gave Poulson contracts for the redevelopment of London Waterloo, Cannon Street and East Croydon stations–all in return for £253 a week and the loan of a Rover car.

Such corruption breeds more corruption; it was estimated at Poulson’s trial that 23 local authorities and over 300 individuals were involved. But the corruption had other deleterious effects. Taxpayers’ money was misused in paying more than the contracts might have cost on an open public tender.

The businesses that genuinely deserved to be awarded such contracts suffered. The public, who might have had buildings to admire, instead saw their city centres blighted by some of the worst examples of sixties brutalist architecture. Mercifully, most of the city centres of Newcastle and Leeds have since again been redeveloped, as has Cannon Street station; but some horrendous examples remain.

Towards stronger laws

The Bribery Act 2010 repealed and replaced a number of statutory and common law offences relating to bribery, some of which were over 100 years old. They had been subject to some criticism by the OECD for being out of date.

Prior to the Bribery Act 2010, the courts relied upon the common law offence of corruption. This defined corruption as “the receiving or offering of any undue reward, by or to any person whatsoever, in a public office in order to influence his behaviour in office, and incline him to act contrary to the known rules of honesty and integrity.” The problem with this common law offence was that it applied only to a person in a public office. Plus undue reward was not defined in any way. But despite this drawback, the courts tended to construe the offence as widely as possible, albeit business to business bribery often went unpunished.

There have been a series of attempts to strengthen the law since Victorian times, such as through The Prevention of Corruption Act 1889 and The Prevention of Corruption Act 1906, but these laws did not address the private sector or international corruption. There were further attempts in 1997, when a large number of EU member states signed The Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials. But the focus of this was on active bribery, targeting the supplier of the bribe and not the recipient. Plus it was expressly restricted to foreign public officials.

Subsequent legislation in 2001, 2003 and 2004 still did not fully address the problems or inconsistencies in The Prevention of Corruption Acts. There was no definition of corruption in any act, and the distinction between the public and private sectors was increasingly untenable. Prosecutors found it increasingly difficult to establish corporate liability, the so-called ‘controlling mind’ problem. These issues, combined with pressure from Europe and the growing concern of the widespread reach and impact of corruption with its links to organised crime, led to the overhaul of the UK’s legislation on corruption, leading to the Bribery Act 2010.

What’s the international angle?

Before the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention was signed in 1997, there was no effective multinational framework for the prevention and prosecution of bribery.

But more than 20 years since the Convention’s implementation, nearly 800 companies and individuals have received sanctions for foreign bribery, at least 125 individuals put behind bars, and over 500 investigations undertaken in 30 countries.

The Convention has also been a catalyst for ensuring those who expose wrongdoing are better protected and for the widespread adoption of legislation to ensure that companies – not just individuals – can be held to account for unlawful behaviour, not only for foreign bribery. This has forced many companies worldwide to adopt or strengthen their ethics and compliance programmes in order to detect and prevent improper conduct.

A landmark example is the successful sanctioning in 2016 of the global construction conglomerate, Odebrecht, and its subsidiary, which resulted in the largest ever penalty imposed in a foreign bribery case, totalling USD 3.5 billion. Brazil, Switzerland and the United States, all signatories to the Anti-Bribery Convention, worked together on what the US Department of Justice called “the largest foreign bribery case in history”. The record fine served to compensate the victims and to fill public coffers. Brazil’s commitments under the Anti-Bribery Convention also helped propel the adoption of a new law in 2014, which enabled Brazil to hold companies like Odebrecht accountable for corrupt practices, both at home and overseas.

What’s the impact been?

Freedom of information requests have revealed that, after ten years, there have been nearly 100 convictions under the Bribery Act, however only two of those convictions have been made against corporates for the failure to prevent bribery offence under section 7 of the 2010 Act.

The majority of the Serious Fraud Office’s (SFO) wins in relation to bribery principally relate to the use of deferred prosecution agreements, which set out a statutory mechanism that allows investigations into fraud, corruption and other crime committed by corporate organisations to be concluded without prosecution. A DPA is made between an organisation and the prosecuting authority and is supervised by a judge.

Last year, the House of Lords completed its ten year review of the 2010 Act. While they were resoundingly positive in their assessment, the Lords did recommend a clarification of adequate procedures for the purposes of establishing the section 7 defence. One possible suggestion was that it should be interpreted to mean “reasonable in all the circumstances”, which echoes section 45.

The committee also suggested greater clarity as to where the dividing line should be between what is considered legitimate corporate hospitality and what would be considered as bribery. This was in the context of the fact that government guidance on these topics is perceived to be inadequate, which can contribute to a misinterpretation of these terms.

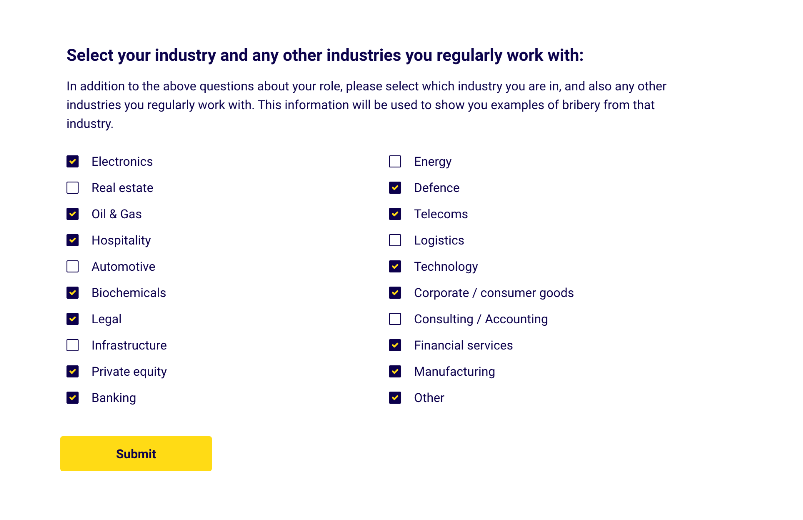

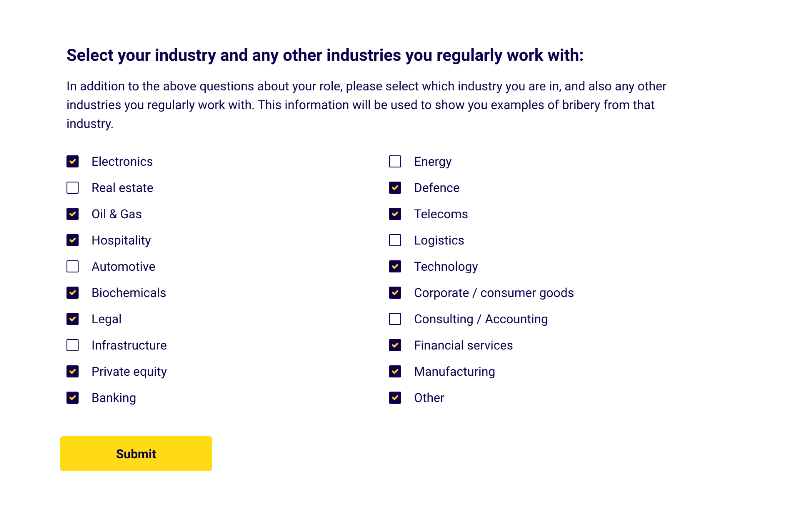

VinciWorks’ new anti-bribery training

It’s imperative that all organisations offer annual bribery training as part of their adequate procedures. VinciWorks will soon be releasing a new bribery course, Anti-Bribery: Fundamentals. The course is suitable for all types of users in an organisation, from rookies to veterans, and includes a unique course builder at the start, so every user completes their own personalised course, individually tailored to their training requirements.