The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region faces a wide range of AML risks due to a combination of geopolitical instability, corruption, and vulnerabilities in financial systems. Many countries in the region serve as hubs for trade, banking, and finance, which can be exploited for illicit financial flows, including terrorist financing, trade-based money laundering, and smuggling activities.

While some nations, such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, have made significant efforts to strengthen their AML frameworks and comply with Financial Action Task Force (FATF) recommendations, enforcement remains inconsistent across the region. Countries affected by conflict, such as Syria, Yemen, and Libya, face heightened risks due to weakened state institutions and limited regulatory oversight.

Key challenges in the region include cash-based economies, informal financial networks (e.g., hawala systems), and difficulties in monitoring cross-border transactions. Despite ongoing reforms and international cooperation, continued efforts to enhance beneficial ownership transparency, customer due diligence, and financial intelligence capabilities are essential to mitigate AML risks in the region effectively.

Understanding national money laundering risks

Money laundering risks refer to the vulnerabilities within a country’s systems that criminals can exploit to integrate illicit financial gains into the legitimate economy. These risks stem from systemic weaknesses such as insufficient legal frameworks, corruption, lack of transparency, ineffective enforcement measures such as a weak police or judiciary, and political corruption.

At its core, money laundering enables crimes ranging from drug trafficking and fraud to terrorism financing. The interconnected nature of global financial systems means that these risks often transcend borders, impacting not just individual countries but the global economy at large.

Risks in one country can easily spill over into connected jurisdictions, as criminals exploit weaker systems to hide the profits of criminal enterprise into the legitimate economy. It is important for any firm which has the potential to be exploited for money laundering to understand the risks for each jurisdiction linked to transactions or clients they work with.

How should money laundering risks be categorised?

The Basel AML index provides a holistic view of country risks. It categorises risks based on five different areas, with different weighting given to each:

Quality of AML/CFT/CPF framework (50%): This includes compliance with international standards such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations. Factors assessed include customer due diligence, reporting suspicious transactions, and the implementation of financial sanctions.

Corruption and fraud risks (17.5%): Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index and indicators of financial crimes and cybercrimes provide a snapshot of the level of corruption and fraud in a jurisdiction.

Financial transparency and standards (17.5%): Indicators like the Financial Secrecy Index assess the openness of financial systems and the risk of financial institutions being exploited for illicit purposes.

Public transparency and accountability (5%): This domain evaluates public access to budget information, transparency of political financing, and accountability mechanisms in public institutions.

Political and legal risks (10%): Key indicators include judicial independence, the rule of law, media freedom, and political rights. Weaknesses in these areas can significantly exacerbate money laundering risks.

To measure a country’s risk level, the Basel AML Index uses a composite scoring methodology that integrates data from 17 publicly accessible indicators. These scores are summarised on a scale from 0 to 10, where 10 represents the highest risk.

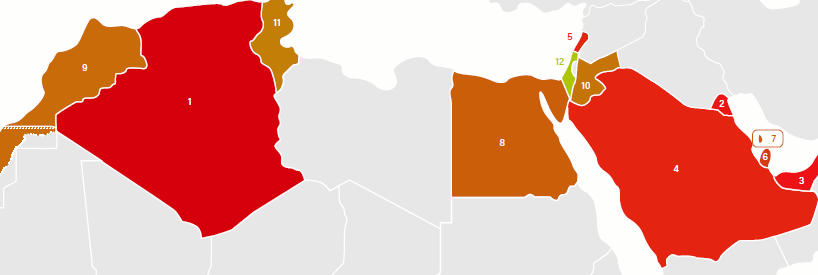

The highest risk countries in the Middle East and North Africa for money laundering

Algeria (Score: 6.92)

Algeria faces high AML risks due to widespread corruption, weak enforcement mechanisms, and an underdeveloped financial oversight framework. Despite efforts to strengthen its AML regime, including recent reforms aimed at improving compliance with FATF standards, enforcement remains limited, particularly in high-risk sectors such as real estate, trade-based money laundering, and cash-based transactions. Algeria’s largely state-controlled economy also poses challenges, as outdated banking systems and weak governance create opportunities for illicit financial flows. While improvements have been made, Algeria was added to the FATF grey list in 2024, indicating the need for further reforms, particularly in enhancing beneficial ownership transparency and supervision of high-risk sectors.

Kuwait (Score: 6.27)

Kuwait’s AML risks are primarily linked to its cash-intensive economy, lack of transparency, and exposure to trade-based money laundering. Although Kuwait has implemented a legal framework in line with FATF recommendations, weaknesses persist in customer due diligence and monitoring politically exposed persons (PEPs). The country’s reliance on remittances and informal money transfer systems increases vulnerabilities, particularly as it serves as a regional hub for financial transactions. While Kuwait has made efforts to address these issues, enforcement remains inconsistent, and gaps in beneficial ownership reporting leave room for illicit activities. Continued reforms and improved financial intelligence unit (FIU) capabilities are required to mitigate these risks.

United Arab Emirates (Score: 6.18)

The UAE, despite being removed from the FATF grey list in February 2024, remains on the EU’s high-risk jurisdiction list, reflecting ongoing concerns about beneficial ownership transparency, corporate secrecy, and its status as a global financial hub. The country’s advanced economy and strategic role in international trade make it vulnerable to trade-based money laundering, real estate investment abuse, and shell companies used to hide illicit funds. The UAE has made significant reforms, including strengthening its AML laws, improving customer due diligence practices, and enhancing supervisory frameworks, but enforcement gaps remain. Its continued listing by the EU highlights concerns over suspicious transaction monitoring and the effectiveness of regulatory oversight, particularly in free trade zones and offshore financial services.

Saudi Arabia (Score: 5.88)

Saudi Arabia has taken steps to strengthen its AML framework, benefiting from its strategic partnerships with global organisations and adherence to FATF standards. However, vulnerabilities persist due to cash-based transactions, corruption risks, and the country’s role as a financial centre in the Gulf. Saudi Arabia faces challenges related to terrorist financing and the misuse of charities to funnel illicit funds. While regulatory improvements have enhanced customer due diligence and beneficial ownership transparency, gaps in enforcement and monitoring politically exposed persons (PEPs) remain.

Lebanon (Score: 5.81)

Lebanon was added to the FATF grey list in 2024, highlighting its increased vulnerabilities due to economic collapse, political instability, and weak regulatory enforcement. The country’s financial sector has long been a gateway for terrorist financing, corruption, and trade-based money laundering, with Hezbollah’s influence raising concerns about illicit finance networks. Lebanon’s banking secrecy laws have historically shielded illicit funds, although recent reforms have aimed to increase transparency. However, the country’s ongoing financial crisis and lack of effective enforcement continue to pose significant AML challenges. Being added to the FATF grey list means enhanced due diligence must be applied.

The lowest risk countries in the Middle East and North Africa for money laundering

Egypt (Score: 5.08)

Egypt faces moderate AML risks, primarily driven by corruption, informal economies, and trade-based money laundering. As a regional hub for trade and remittances, Egypt is vulnerable to cash-based transactions and hawala systems, which operate outside formal financial channels. While Egypt has made progress in strengthening its AML framework and aligning with FATF standards, enforcement remains inconsistent, particularly in beneficial ownership transparency and customer due diligence. The country’s geographic position also makes it susceptible to terrorist financing and cross-border smuggling, requiring enhanced monitoring and international cooperation to mitigate these risks.

Morocco (Score: 4.94)

Morocco has a comparatively lower AML risk than some of its regional counterparts, but it still faces challenges related to corruption, drug trafficking, and trade-based money laundering. The country serves as a transit route for illicit activities between Europe and Africa, making it vulnerable to cross-border financial crime. Morocco has taken steps to modernise its AML framework, including improved customer due diligence and stricter reporting requirements for suspicious transactions. However, weaknesses in enforcement mechanisms and gaps in beneficial ownership disclosure persist. Continued reforms and international cooperation are essential to further reduce these vulnerabilities.

Jordan (Score: 4.81)

Jordan exhibits relatively moderate AML risks, largely due to its strategic location near high-conflict zones and its role as a financial and trade centre in the Middle East. The country’s AML vulnerabilities stem from terrorist financing, corruption, and money laundering through trade and remittance systems. While Jordan has implemented reforms to strengthen its AML compliance and align with FATF standards, enforcement gaps remain, particularly in monitoring non-financial sectors and improving beneficial ownership transparency. Jordan’s reliance on cash-intensive businesses and its role as a gateway for humanitarian aid to conflict zones require sustained efforts to mitigate financial crime risks.

Tunisia (Score: 4.77)

Tunisia is a lower-risk jurisdiction in the region, benefiting from recent AML reforms and increased alignment with international standards. However, vulnerabilities persist due to political instability, corruption, and weak enforcement mechanisms. The country’s reliance on cash-based transactions and informal financial systems poses ongoing challenges, while trade-based money laundering and terrorist financing remain key risks. Tunisia has strengthened its regulatory framework, but implementation gaps and weaknesses in monitoring politically exposed persons (PEPs) continue to undermine its AML efforts. Further reforms and stronger enforcement are needed to sustain progress.

Israel (Score: 3.97)

Israel stands out as the only democracy in the region and maintains significantly lower AML risks compared to its neighbours. As a global centre for high-tech innovation, trade, finance, and entrepreneurship, Israel’s robust legal and regulatory frameworks provide strong safeguards against money laundering. The country has implemented comprehensive AML measures, including customer due diligence, suspicious transaction reporting, and beneficial ownership transparency. Israel’s advanced cybersecurity infrastructure and financial intelligence units further bolster its defences against illicit financial flows. Unlike other countries in the region, Israel does not face the same levels of corruption, terrorist financing, or informal cash economies, making it a more secure jurisdiction for financial activities. However, as a global financial hub, Israel remains vigilant against emerging risks such as cybercrime and trade-based money laundering, ensuring it maintains its low-risk profile through continuous innovation and regulatory enhancements.

Looking for more information on high risk countries for money laundering? Download our comprehensive guide to high risk jurisdictions for AML and understand the steps your firm should take.