As the World Cup continues in Qatar, the event is being closely watched. Not only in terms of results of fixtures, but in the cost of human life.

Due to the complexity and invisibility of forced labour and modern slavery in the supply chain, it’s impossible to close in on an exact number of people entrapped in these conditions today, but it is estimated that around 40 million people are trapped in forced labour worldwide in various forms.

This includes millions of people who are exploited in forced labour in the private sector as well as millions who are subjected to state-imposed forced labour. These people are part of the supply chains of international businesses supplying our goods and services, and are enslaved and exploited in countries such as China, Afghanistan, India, China, Pakistan and North Korea, as well as in developed countries, where modern slavery exists often just out of sight for most people. Additionally, Russia’s war against Ukraine has displaced hundreds of thousands of people, making them vulnerable to traffickers who can easily abduct them for exploitation.

Meanwhile, as millions tune in to support their teams in this year’s World Cup in Qatar, many might not be aware of the extent to which forced labour was involved in its production. Qatar’s dreadful human rights record has only descended further into darkness with its appalling treatment of the migrant workers who built the stadiums and other new infrastructure as part of the preparations for the current games. It is convenient to ignore and unpleasant to confront the reality of the World Cup built on modern slavery. Throughout the decade of preparation for this year’s tournament, thousands died and an estimated 100,000 migrant workers were exploited and suffered abuse because of lax labour laws and insufficient access to justice in Qatar in the past 12 years. Construction workers reveal how when FIFA inspectors arrived, they were forced to hide.

The World Cup in numbers

$200bn

This is the amount that Qatar is reported to have spent on the production of the World Cup. For comparison, Russia spent around $11bn in 2018.

0

Neither FIFA nor the Qatar authorities requested any human rights clauses or conditions relating to labour protections when awarding the hosting rights to Qatar in 2010.

100,000

Amnesty International estimates that at least 100,000 migrant workers have been exploited and suffered abuse because of weak labour laws and insufficient access to justice in Qatar in the past 12 years.

6,500

At least 6,500 migrant workers from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka died in Qatar between 2010, when the country was awarded the World Cup, and 2021. The actual number is surely much higher, and will never be known.

3

Only three official worker deaths were reported in Qatar during the preparations for the World Cup 2022.

14-18

According to Amnesty, this is the number of hours many migrant workers are forced to work in Qatar, especially in the domestic and security sectors, with no paid overtime. This has been reported as being the case for those working on the production of the stadium and other World Cup-related infrastructure as well.

$440m

This is the amount that Amnesty and others believe FIFA should distribute to migrant workers who have suffered or to the families of workers who died: this amount is equivalent to the World Cup’s prize money. But Qatari’s labour minister has rejected such proposals, saying there was “no criteria to establish these funds”, and that criticism of the government is “racist”.

Case study: Anish Adhikari

Anish Adhikari came to Qatar in 2019 with the promise that he would make $8,000 over three years, which he could use to support his family in Nepal and pay back the loan shark who’d secured him the job with the Hamad Bin Khalid Contracting co, owned by Qatar’s own ruling Al Thani family. The living conditions were squalid, and he was made to work 14 hour days in 51℃ heat with limited water available, causing a range of health ailments including swollen tonsils, diarrhoea, vomiting and heart palpitations. Still, he thought of his family back in Nepal: his father and sickly mother, who lived in a hurricane-ravaged house with an animal shed as a kitchen along with his six brothers, their four wives, and their eight children, and this kept him hopeful that by working to build air conditioners for 80,000 ticket holders he’d earn the money he needed to support his family back home and pay back the loan sharks. But some days, it was too much. He also found that 95% of his recruitment expenses, his employee benefits, and two-thirds of his salary had vanished. At first, he was able to complain about the working conditions to a representative from Qatar’s local Supreme Committee in charge of the tournament. Soon, though, HBK managers disinvited outspoken employees from worker-welfare forums.

Case study: Sunit

Sunit planned to be in Qatar for two years. He had dreamed of staying in Qatar for the World Cup and watching the games from the roof of the hotel he would help build. But his dreams were shattered when the construction company he worked for collapsed and he and many others that worked there were forced to return home after just 7 months with money still owed to them. Now back in Nepal, he struggles to find work to feed and pay school fees for his two children. While he was in Qatar, the working conditions were gruelling. His job involved carrying bags of plaster mix and cement that weighed from 30 to 50 kilos up 10 to 12 floors. The lift was rarely functional. Some people couldn’t bear the weight and would put down or drop their loads, and then were threatened with a reduction in their salary. In addition, they worked in unbearable heat and were shouted at and threatened with a loss of the day’s wages for taking water breaks or working slowly. He has filed a case with police about the agent as his contract was not fulfilled and his wages remain unpaid, but has yet to receive any response.

Some workers never returned

Unfortunately, these stories are not rare, and in addition to these stories of forced labour under inhuman conditions, it is estimated that at least 6,500 South Asian migrant workers have died in Qatar since the country was awarded the World Cup in 2010, and probably more: as fatal heat stroke can often look like a heart attack or a seizure, and can also amplify existing, otherwise manageable conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, Qatar has been able to deny the correlation between heat stress and deaths and claim that the deaths in many cases were due to natural causes. In addition, it is difficult to determine the number of injuries caused by heat stress, as sometimes injuries might not become apparent until years later. This makes it difficult for workers or their families to be eligible for compensation.

While there has been some progress in recent years with regard to raising awareness about modern slavery and child labour involved in industries such as clothing production and food including the meat, coffee, and chocolate we eat, there has been much less of a spotlight shown on the treatment of workers involved in the production of mega events such as the World Cup. Because those being exploited are often migrant workers from poor south Asian counties, they are invisible to most.

Improvements to employment law are too little, too late

Qatar’s Supreme Committee for Delivery & Legacy (SC) claims that it investigates all deaths and established a Workers’ Welfare Forum that allows workers to elect a representative to complain, alert authorities, and demand better conditions, but while there have been a few positive changes to Qatar employment law since the committee was established in 2015, much work remains to be done. Families of workers who died face an uphill battle in receiving compensation money and workers that survived and returned home, often cheated out of the wages they were promised, remain trapped in debt.

How can we fight modern slavery?

Modern countries such as the UK, US, and Australia are fighting human trafficking with legislation that makes it harder to use and profit from forced labour, and slowly, more and more countries are catching on and taking action.

Canada and New Zealand are among the countries expected to approve modern slavery acts in the coming months. In the UK, since 2015, the Modern Slavery Act has required many large companies to produce an annual statement. But it is time for companies to go further than the minimum legal standards. Qatar has driven focus to the fact that human rights abuses can often be ignored when billions of dollars are at stake. Few companies wish to be put in such a position, and away from the sporting aspect of the World Cup, millions of fans who may have otherwise enjoyed the football spectacle, have been grossly offended by the ongoing human rights abuses in Qatar, and are turning against those companies which are supporting the country’s World Cup.

The challenge

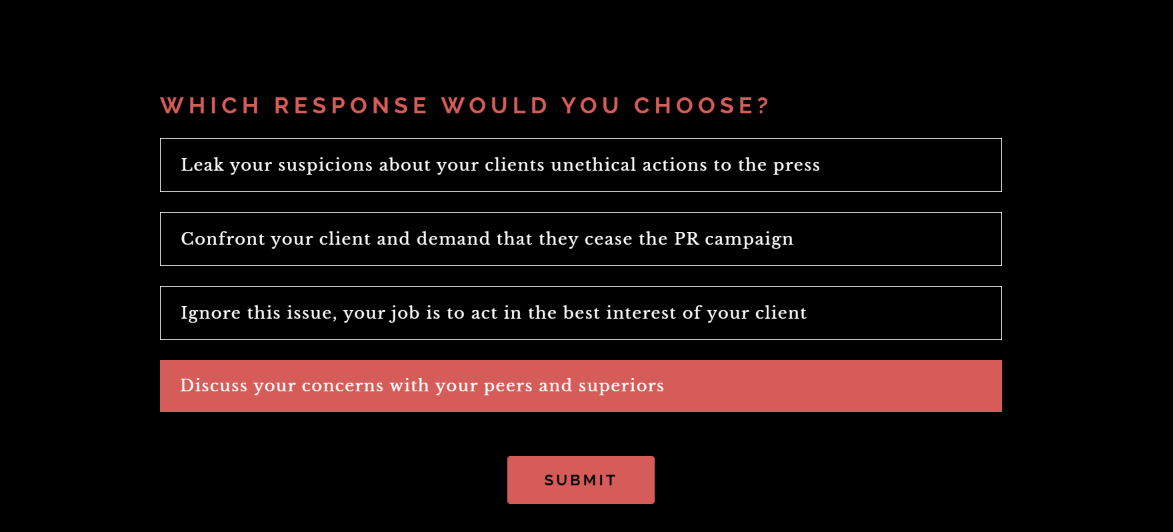

More and more organisations are waking up to the importance of fighting modern slavery, and the importance of robust workforce training and company record keeping, but it can be difficult to gauge the level of risk with each supplier, and this poses a challenge for businesses. Businesses that distribute supplier questionnaires via long PDF and Excel forms will struggle to ensure red flags don’t slip through the cracks, and missing out vital information could lead to huge fines and irreparable damage to your business’ reputation.

How VinciWorks can help

VinciWorks has built a best-practice modern slavery reporting solution that allows businesses to collect all necessary data from their suppliers, easily flag high-risk countries and take any action required to reduce the risk of slavery in the supply chain.

In addition, our modern slavery training suite offers a variety of training options for companies to use as part of their internal compliance programs. Our courses are designed to meet the needs of an entire organisation, from general staff to procurement teams.

Click here to learn more about our solutions.